Civil Disobedience and Student Protest in Mid 20th Century New Haven

By Ethan Mehlin

The post World War Two era in America often remembered as a time marked by protest and civil unrest. The causes of this discontent were varied, many protests focused on the draft and the military, while others were directed at racial issues and discrimination. Oftentimes these protests were spearheaded and held campuses, with students organizing and leading acts of civil disobedience. Occurring across the country, New Haven was no exception and found itself home to a series of protests at the Yale campus in the Late 1960’s. Led by the Black Student Law School (BLSU), the group centered their efforts on demanding reform for the New Haven police force whom often arrested and harassed black students with no cause. Over the coming weeks, the BLSU would lead several in class demonstrations as well as present demands to the Yale administration. Despite ineffectual responses from Yale, the BLSU would persist in its efforts and even found itself joined by the majority of the white student body, who presented articles to Yale announcing their support of the BLSU. While the discontent among the students would not be quelled by Yale and eventually lead to the 1970 May Day Protest, the response of the students to abuse of authority from the police as well as the solidarity between the black and white students indicates a remarkably progressive attitude in a relatively conservative era. Especially with the continuity of the issues the students protested into the modern day, the Yale 1960’s and 1970’s protests provide an enlightening view on how students of urban institutions responded to several different authorities.New Haven in the 1960’s was a relatively tumultuous time in regards to race relations. Urban redevelopment headed by the Mayor of New Haven was often aimed at destroying and isolating minority neighborhoods, fostering tension between these people and the government of the city. Discrimination by the police force, as well as heavy handed tactics when dealing with protests from largely minority neighborhoods, also led to a distrust of law enforcement in the city. These feelings extended to student populations at the local colleges, especially at Yale. Students who found themselves in groups at night on the streets were often harassed for no reason by police officers, especially if they started questioning the officers. Unhappy with how they were being treated, members of the BLSU presented a list of demands to the Yale administration, asking for a comprehensive study into the policing problem in New Haven and America as a whole, as well as hiring of police officers equivalent to the black population of the city. They also called for a civilian review board of the police department, to provide oversight for their actions. While these demands were submitted, several students disrupted class with chants of “Stop the Cops”. After several of these students were threatened with disciplinary action, many of the white law students met to discuss the situation. They agreed after several hours to stage either a boycott or strike, and also sent a letter to Yale administration unequivocally stating their support for the actions of the BLSU.

The events that occurred at Yale in 1969 are extremely useful in understanding how and why the students protested the way they did. Especially with many of the protests in this era turning to violence, having records of the BLSU and their nonviolent approach to civil disobedience demonstrates some of the different ways protests can take shape. In addition to non violent tactics, the BLSU’s demands were also surprisingly beneficent. Of course they called for police review in their own city, but they also asked Yale to use a recent endowment for urban studies to study the policing problem in America as a whole. The students who protested at Yale didn’t just want to improve their own existences, rather they wanted everybody to be afforded the same treatment by the law. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the student body at Yale was without a doubt one of the more progressive segments of the population. Evidenced by the fact that the white students at Yale reached a near consensus on supporting the BLSU, these events show that civil disobedience can be undertaken through measured and relatively peaceful means.

When taken in context with the present day, the events at Yale take on a disheartening tone. The injustices being protested by the students still exists today, not to the same extent as the 1960’s but certainly still widespread across the nation. The BLSU demands, if submitted today, would be indistinguishable from a modern day proposal. Societal progress and acceptance is generally not a quick road, but the futility of the Yale protests shows that good intentions don’t equal good results. Yale did not give in to the BLSU demands, and cooperation between the BLSU and the local Black Panther chapters would lead to the much larger and more violent May Day riots in 1970. These would eventually force Yale to capitulate and meet some of the students demands, but many of the underlying problems the students were hoping to address remained unsolved. While their actions certainly led to some success, their setbacks highlight the immense challenges of trying to bring societal change.

|

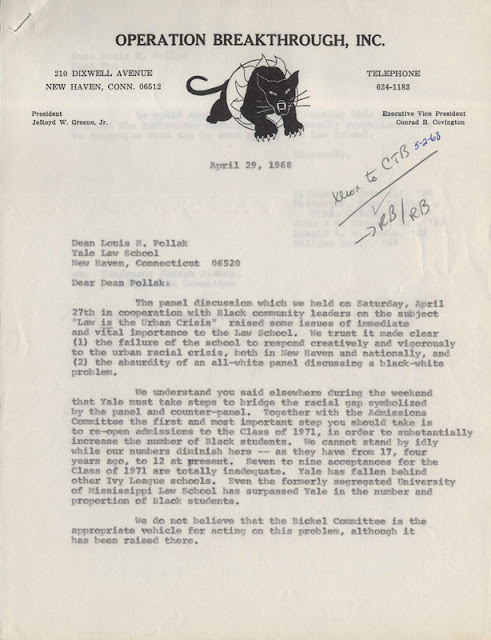

| A letter addressing dissatisfaction with education in New Haven, Courtesy of Yale University Library |

|

| A Yale journal covering student civil disobedience during the 1960's Courtesy of Yale University Library. |

Bibliography

Operation Breakthrough, Inc., correspondent.,

“First page of a letter to Dean Louis Pollak from Operation Breakthrough, Inc. regarding issues raised at a Yale Law School community panel discussion on the urban crisis, especially “the absurdity of an all-white panel discussing a black-white problem.” ,”

Yale Alumni Magazine., “"Student Strike at Law School Centers on Police Harassment, Governance,"

article from Yale Alumni Magazine, Volume 33, Number 2, page 20. ,”

Comments

Post a Comment